A novel 5mC-directed site-specific DNA endonuclease MoxI efficiently cleaves the DNA sequence 5′-R(5mC)GY-3′

V.A. Chernukhin, V.S. Dedkov, D.A. Gonchar, V.N. Baimak, O.A. Belichenko, S.Kh. Degtyarev

V.A. Chernukhin, V.S. Dedkov, D.A. Gonchar, V.N. Baimak, O.A. Belichenko, S.Kh. Degtyarev

SibEnzyme Ltd, Novosibirsk, Russia

* Corresponding author: S.Kh. Degtyarev, SibEnzyme Ltd., 2/12 Ak. Timakova Street, Novosibirsk 630117, Russia, E-mail: degt@sibenzyme.com

Abstract

A bacterial strain of Microbacterium oxydans was identified as a producer of a 5-methylcytosine-dependent, site-specific DNA endonuclease, MoxI. The enzyme recognizes and cleaves the DNA sequence 5′-R(5mC)↓GY-3′ / 3′-YG↓(5mC)R-5′.

The moxI gene was cloned and expressed in Escherichia coli, and the recombinant enzyme was purified and biochemically characterized. The recognition sequence of MoxI was shown to be identical to that of the previously described 5mC-directed site-specific DNA endonuclease GlaI. In contrast to GlaI, however, MoxI exhibits maximal catalytic activity at 37 °C and demonstrates higher cleavage efficiency toward substrates containing two 5-methylcytosine residues within the recognition site.

Keywords: producer strain, 5mC-directed site-specific DNA endonuclease, epigenetics

DOI: 10.26213/3034-4301.2025.6.3.001

Citation:

V.A. Chernukhin, V.S. Dedkov, D.A. Gonchar, V.N. Baimak, O.A. Belichenko, S.Kh. Degtyarev (2025) A novel 5mC-directed site-specific DNA endonuclease MoxI efficiently cleaves the DNA sequence 5′-R(5mC)GY-3′ // DNA-processing enzymes, vol 2025(3), DOI: 10.26213/3034-4301.2025.6.3.001

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License

INTRODUCTION

Methyl-directed site-specific DNA endonucleases (MD-endonucleases; MD = methyl dependent) are enzymes that recognize and cleave specific methylated DNA sequences and do not hydrolyze unmodified DNA [1]. In their properties, these enzymes resemble the well-studied restriction endonucleases, since, similarly to them, they do not require cofactors other than Mg²⁺ ions to exhibit activity. The enzyme GlaI that we previously discovered, isolated from the bacterial strain Glacial ice bacterium, is an MD-endonuclease that recognizes the sequence 5′-R(5mC)GY-3′/3′-YG(5mC)R-5′ in natural DNA and cleaves both DNA strands in the middle of the site, generating blunt ends [2]. Mammalian and human DNA methyltransferase DNMT3 catalyzes de novo DNA methylation to produce the sequence 5′-R(5mC)GY-3′/3′-YG(5mC)R-5′ [3], which is the recognition site of GlaI. As a consequence, GlaI has found application in epigenetic DNA diagnostics and is used to determine the methylation status of individual sites or DNA fragments [4,5], as well as for human epigenome mapping [6]. In the present study, we describe the isolation of a new MD-endonuclease, MoxI, define the optimal conditions for DNA hydrolysis by this enzyme, and compare the properties of MoxI and GlaI.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents from Sigma-Aldrich (USA), Thermo Fisher (USA), Panreac (Spain), Dia-M and Helicon (Russia) were used throughout this study. The following matrices were employed for chromatographic purification of the enzyme: phosphocellulose P-11 (Whatman, UK), phenyl-Sepharose, and heparin-Sepharose (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). Components of bacterial growth media were purchased from Organotechnie (France). Restriction endonucleases, T4 bacteriophage polynucleotide kinase, and SE reaction buffers B100, B, G, O, W, Y, and ROSE were obtained from SibEnzyme Ltd. (Russia). DNA size markers 1 kb, 100 bp, and pUC19/MspI (SibEnzyme, Russia) were used for agarose and polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. For dilution of recombinant GlaI and MoxI preparations during activity measurements, the SE enzyme storage/dilution buffer B100 was used (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6; 50 mM KCl; 0.1 mM EDTA; 200 μg/mL BSA; 1 mM DTT; 50% glycerol). Plasmid DNAs pMTL22 [7], pUC19 [8], and pHspAI2 [9] served as substrates.

Assays of activity and substrate specificity of recombinant MoxI were performed in 20 or 50 μL reaction mixtures containing SE buffer Y (33 mM Tris-acetate, pH 7.9; 10 mM magnesium acetate; 66 mM potassium acetate; 1 mM DTT) and 1 μg of substrate DNA, incubated at 37°C for 1 h, followed by PAGE analysis. To monitor MoxI activity during chromatography, 1-μL aliquots of fractions were added to 20 μL reaction mixtures containing 1 μg of pHspAI2/GsaI DNA in SE buffer Y; mixtures were incubated for 15 min at 37°C and analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. To test the activity of the purified MoxI preparation, either 1 μL of undiluted enzyme or 0.5, 1, and 2 μL of enzyme diluted 10-fold in SE buffer B100 were used. The enzyme was added to 50 μL reaction mixtures containing 1 μg of pHspAI2/GsaI DNA and one of six reaction buffers for restriction endonucleases (B, G, O, W, Y, ROSE). Reactions were incubated for 1 h at 25, 30, 37, or 55°C, then terminated by addition of stop buffer (40% sucrose, 0.1 M EDTA, 0.05% bromophenol blue) and analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Morphological and physico-biochemical properties of the original producer bacterium were determined using standard methods [10]. The genus of the microorganism was assigned based both on sequencing of a PCR fragment of the 16S rRNA gene and on Bergey’s Manual [11].

To determine the phosphodiester bond cleavage position catalyzed by MoxI, two [^32P]-labeled DNA duplexes (G3/G4 and G3/G2) containing the recognition site of the target enzyme and recognition sites for control restriction enzymes were used. One strand of each duplex (G3) was 5′-end labeled with T4 polynucleotide kinase and γ[^32P]ATP. After removal of reaction by-products, the labeled oligonucleotide was annealed with the complementary unlabeled oligonucleotide G4 (for GlaI and MoxI) or G2 (for HspAI and AspLEI). Tubes were heated for 5 min at 95°C and then allowed to cool to room temperature on the bench. Cleavage reactions were carried out in 10 μL mixtures containing SE buffer Y (with 20% DMSO in the case of GlaI) or SE buffer O, the oligonucleotide duplex at 62.5 nM, and 1 μL of the corresponding enzyme, and incubated for 1 h. GlaI cleavage was performed at 25°C, whereas MoxI cleavage was performed at 37°C in SE buffer Y. Control reactions contained either SE buffer Y and 1 μL of HspAI, or SE buffer O and 1 μL of AspLEI, and were incubated at 37°C. Cleavage products were resolved by electrophoresis in 20% denaturing PAGE containing 8 M urea in Tris–borate buffer; the same system was used for separation of labeled oligonucleotide digestion products.

The recombinant strain E. coli ER2267(pMTL-MoxI) carrying plasmid pMTL22 with the cloned moxI gene was constructed using standard genetic engineering procedures [12]. The Escherichia coli ER2267 host strain used for cloning was obtained from New England Biolabs (USA).

Biomass production of recombinant E. coli ER2267(pMTL22-MoxI) carrying the moxI gene

To produce biomass, a single colony of E. coli ER2267(pMTL22-MoxI) was inoculated into a flask containing 100 mL LB medium (1% tryptone, 0.5% yeast extract, 0.5% NaCl, pH 7.5) supplemented with ampicillin (50 μg/mL) and grown overnight at 37°C. The resulting inoculum was then used to seed twelve flasks containing 100 mL LB medium with ampicillin (5 mL per flask). Cultures were grown for 5 h at 30°C in a thermostated shaker at 140 rpm. IPTG was then added to a final concentration of 1 mM, and cultivation was continued for an additional 20 h. A 1-mL sample of culture was taken for analysis, and the remaining culture was harvested by centrifugation in a J2-21 centrifuge (Beckman, USA) at 6000 rpm for 30 min. The resulting cell biomass was frozen at −20°C.

Isolation of recombinant methyl-directed site-specific DNA endonuclease MoxI

Purification conditions and buffers. Purification was performed at +4°C using the following solutions:

Buffer A: 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 0.1 mM EDTA; 7 mM β-mercaptoethanol.

Buffer B: 60 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 0.1 mM EDTA; 7 mM β-mercaptoethanol.

Extraction. A 2.3-g cell pellet of E. coli ER2267(pMTL-MoxI) was suspended in 25 mL of buffer A containing 0.1 M KCl, 1 mg/mL lysozyme, and 0.1 mM PMSF (phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, a protease inhibitor). After stirring for 60 min on a magnetic stirrer, the suspension (in a 50-mL glass beaker) was cooled in an ice bath and disrupted by sonication at maximum power (amplitude 22–24 μm) using a Soniprep 150 instrument (MSE, UK) equipped with a 2-cm probe: six 30-s pulses with 2-min intervals. The lysate was clarified by centrifugation in a J2-M1 centrifuge (Beckman, USA) for 40 min in a JA-20 rotor at 15,000 rpm.

Phosphocellulose P-11 chromatography. The clarified extract was loaded onto a 50-mL phosphocellulose P-11 column pre-equilibrated with buffer A containing 0.05 M KCl. The column was washed with 100 mL of buffer A containing 0.05 M KCl. Bound material was eluted with a 700-mL linear gradient of 0.1–0.4 M KCl in buffer A. Seventy 10-mL fractions were collected. Fractions 29–35, which contained the highest MoxI activity, were pooled.

Phenyl-Sepharose chromatography. To 70 mL of the active pool, 1 M Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) was added to a final concentration of 60 mM (4.2 mL), and ammonium sulfate was added to 1.7 M (15.7 g). The sample was loaded onto a 5-mL phenyl-Sepharose column equilibrated with buffer B containing 1.7 M ammonium sulfate. The column was washed with 10 mL of buffer B containing 1.7 M ammonium sulfate. The enzyme was eluted with a 600-mL linear gradient of 1.7–0 M ammonium sulfate. Sixty 10-mL fractions were collected, and fractions 37–43 with maximal activity were pooled.

Heparin-Sepharose chromatography. The 70-mL pool was dialyzed against 3 L of buffer A for 16 h and loaded onto a 5-mL heparin-Sepharose column equilibrated with buffer A. After loading, the column was washed with 10 mL of buffer A. The enzyme was eluted with a 400-mL linear gradient of 0–0.15 M KCl in buffer A. Fifty 8-mL fractions were collected. Fractions 18–28 containing maximal MoxI activity were pooled.

Concentration and storage. Active fractions were dialyzed against 900 mL of concentrating buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 0.1 mM EDTA; 7 mM β-mercaptoethanol; 0.2 M KCl; 50% glycerol) supplemented with BSA to 200 μg/mL, with stirring on a magnetic stirrer for 16 h. The preparation was stored at −20°C.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Characterization of the producer strain

The bacterial strain investigated in this study was isolated from a freshwater sample during a search for microorganisms producing restriction endonucleases and MD-endonucleases. Based on morphological and biochemical characteristics and analysis of the 16S rRNA gene sequence (data not shown), the strain was identified as Microbacterium oxydans. The enzyme discovered was designated MoxI according to the accepted nomenclature. The recombinant strain E. coli ER2267(pMTL-MoxI) carrying a plasmid with the moxI gene was obtained by cloning a PCR fragment into the pMTL22 vector.

Preparation of MoxI and analysis of its properties

Cultivation of the recombinant strain E. coli ER2267(pMTL22-MoxI) yielded 2.0 ± 0.5 g/L of biomass. After chromatographic purification, 15 mL of an MoxI MD-endonuclease preparation with an activity of 5000 U/mL was obtained from 2.3 g of biomass. One unit of activity was defined as the minimal amount of enzyme required to completely hydrolyze 1 μg of pHspAI2/GsaI plasmid DNA at the 5′-GCGC-3′ site in a 50-μL reaction mixture in the optimal buffer at 37°C within 1 h.

Substrate specificity of recombinant MoxI

The activity and substrate specificity of the MoxI MD-endonuclease preparation were determined using as a substrate plasmid DNA containing C5-methylated cytosines—pHspAI2 [9], which carries methylated 5′-G(5mC)GC-3′ sites and one 5′-G(5mC)G(5mC)-3′ site—linearized with the restriction enzyme GsaI (pHspAI2/GsaI).

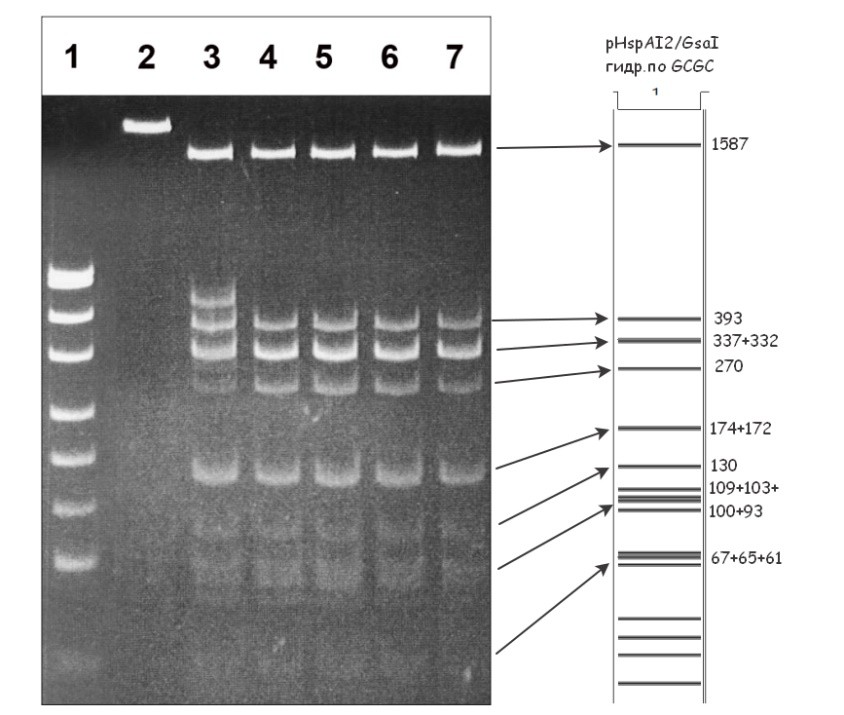

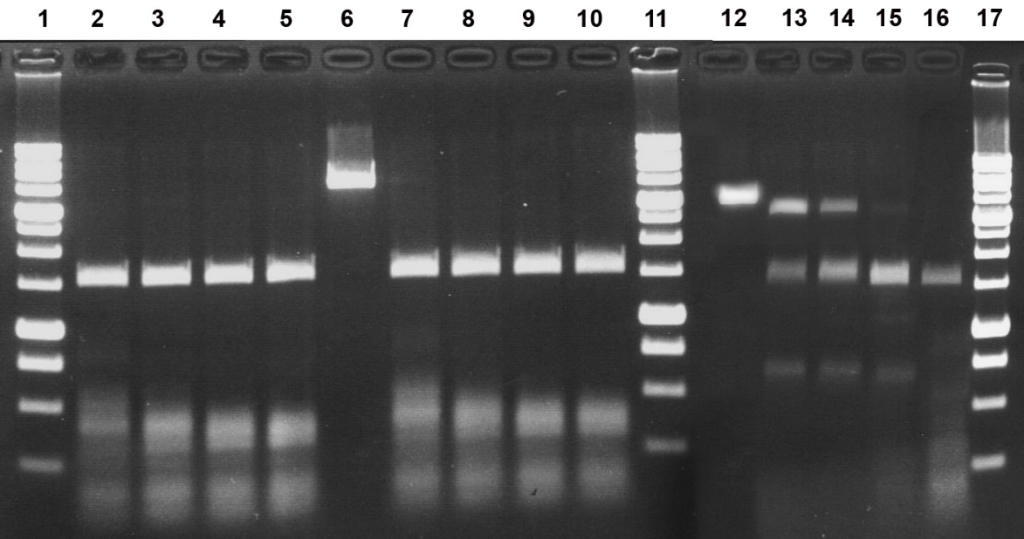

Figure 1A shows an electropherogram of the hydrolysis products of pHspAI2/GsaI plasmid DNA in SE buffer Y at 37°C by GlaI and MoxI, applied individually and in combination. Figure 1B presents, as a specificity control, the results of testing MoxI on λ and T7 phage DNAs, which lack methylated 5′-G(5mC)GC-3′ sites.

Figure 1A. Electrophoretic separation of the hydrolysis products of pHspAI2/GsaI DNA generated by the GlaI and MoxI enzyme preparations, and the predicted fragment pattern resulting from cleavage of this DNA at 5′-GCGC-3′ sites.

Lanes:

- pUC19/MspI DNA marker (26–501 bp);

- undigested pHspAI2/GsaI DNA;

- pHspAI2/GsaI DNA + 1 μL GlaI preparation;

- pHspAI2/GsaI DNA + 1 μL GlaI preparation + 20% DMSO;

- pHspAI2/GsaI DNA + 1 μL MoxI preparation;

- pHspAI2/GsaI DNA + 1 μL GlaI preparation + 1 μL MoxI preparation;

- pHspAI2/GsaI DNA + 1 μL GlaI preparation + 1 μL MoxI preparation + 20% DMSO.

Cleavage products were resolved in 5% PAGE in TAE buffer. The right panel shows the theoretically predicted cleavage pattern of pHspAI2/GsaI plasmid DNA at 5′-GCGC-3′ sites, with fragment sizes indicated (bp).

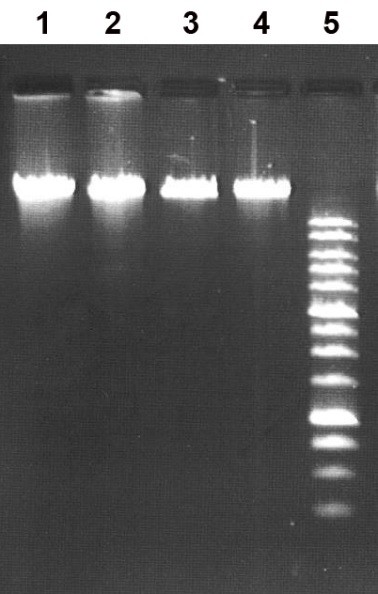

Figure 1B. Electropherogram of λ and T7 phage DNAs after treatment with the MoxI preparation in SE buffer Y at 37°C.

Lanes:

- undigested λ phage DNA;

- λ phage DNA + 1 μL MoxI preparation;

- undigested T7 phage DNA;

- T7 phage DNA + 1 μL MoxI preparation;

- 1 kb DNA ladder (0.25–10 kb).

Cleavage products were resolved in a 1% agarose gel in TAE buffer.

As can be seen in Fig. 1A, digestion of pHspAI2/GsaI DNA by the MD-endonuclease GlaI in the presence of 20% DMSO, digestion by MoxI, and the combined digestion with both enzymes (lanes 4, 5, 6, and 7) yielded identical fragment patterns. This observation unequivocally indicates that both enzymes cleave this methylated plasmid at the 5′-G(5mC)GC-3′ site. Notably, for GlaI the extent of substrate hydrolysis in the absence of DMSO (lane 3) was lower than that observed for MoxI (lane 5), i.e., the new enzyme cleaves the target sequence more efficiently when only the two internal 5-methylcytosines are present. For GlaI, as shown previously [13], complete hydrolysis of a substrate containing two 5-methylcytosines requires the addition of 20% DMSO or the presence of three or four 5-methylcytosines within the recognition site. In contrast, MoxI activity is independent of DMSO (lanes 5 and 7) and the enzyme cleaves DNA containing two, three, or four 5-methylcytosines with comparable efficiency.

Thus, comparison of the MoxI-generated cleavage pattern of pHspAI2/GsaI plasmid DNA shown in Fig. 1A with the theoretically predicted fragment distribution for cleavage at site-specific endonuclease recognition sites supports the conclusion that MoxI hydrolyzes this substrate at the 5′-G(5mC)GC-3′ site and is therefore an isoschizomer of the MD-endonuclease GlaI that we characterized earlier [2,13]. Importantly, like GlaI, the new enzyme does not cleave DNA lacking methylated 5′-G(5mC)GC-3′ sequences (Fig. 1B, lanes 2 and 4).

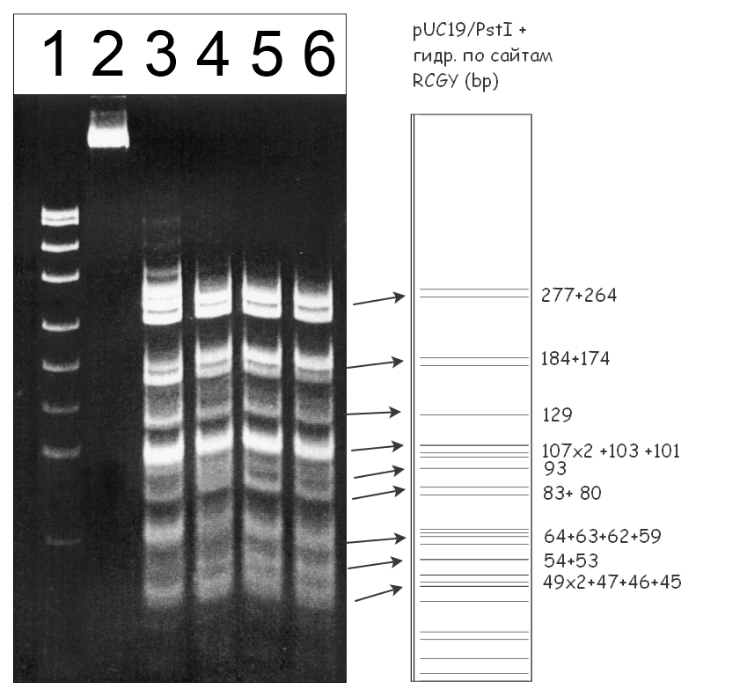

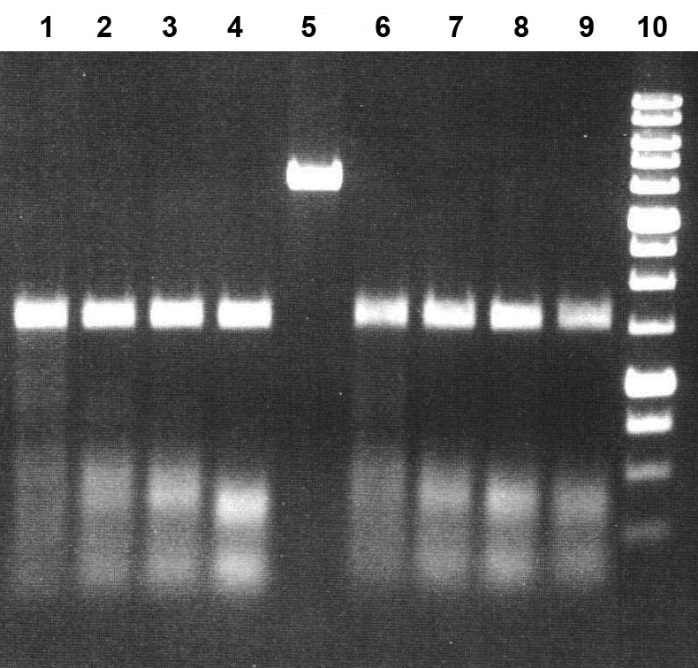

Next, we examined whether the MD-endonuclease MoxI is capable of cleaving not only the 5′-G(5mC)GC-3′ site but also the full set of 5′-R(5mC)GY-3′ sequences recognized by GlaI. For this purpose, we used pUC19 plasmid DNA linearized with PstI and methylated with the DNA methyltransferase SssI, which generates 5′-(5mC)G-3′ methylated sequences. This substrate was treated with GlaI and MoxI, individually and in combination. Figure 2 shows an electropherogram of the resulting hydrolysis products after separation in 7% PAGE.

Figure 2. Electrophoretic separation of the hydrolysis products of pUC19/PstI+M.SssI DNA generated by the GlaI and MoxI enzyme preparations, and the predicted fragment pattern resulting from cleavage of this DNA at 5′-RCGY-3′ sites.

Lanes:

- pUC19/MspI DNA marker (26–501 bp);

- undigested pUC19/PstI+M.SssI DNA;

- pUC19/PstI+M.SssI DNA + 1 μL GlaI preparation;

- pUC19/PstI+M.SssI DNA + 1 μL GlaI preparation + 20% DMSO;

- pUC19/PstI+M.SssI DNA + 1 μL MoxI preparation;

- pUC19/PstI+M.SssI DNA + 1 μL GlaI preparation + 1 μL MoxI preparation.

Cleavage products were resolved in 7% PAGE. The right panel shows the theoretically predicted cleavage pattern of pUC19/PstI plasmid DNA at 5′-RCGY-3′ sites.

As can be seen from Fig. 2, as in the case of pHspAI2/GsaI plasmid digestion, the cleavage patterns of pUC19/PstI+M.SssI DNA produced by the MD-endonuclease GlaI in the presence of DMSO and by MoxI are identical (lanes 4 and 5), and combined digestion of the substrate with both enzymes does not alter the fragment distribution (lane 6). Therefore, the new enzyme MoxI also recognizes the 5′-R(5mC)GY-3′ sequence in DNA.

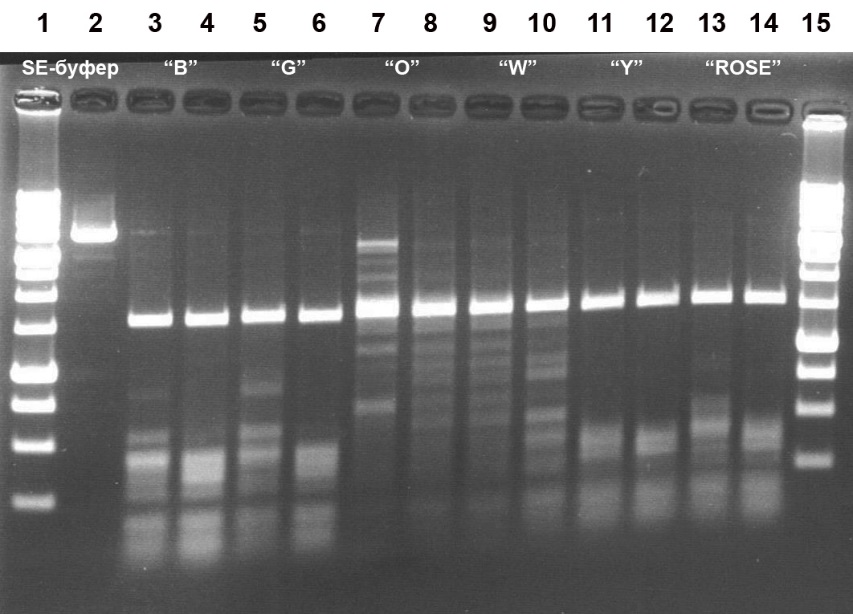

In subsequent experiments, we determined the optimal reaction conditions for the MD-endonuclease MoxI. To this end, reaction mixtures containing 1 μg of pHspAI2/GsaI DNA, one of six buffers for restriction endonucleases (B, G, O, W, Y, ROSE), and 0.5, 1, or 2 μL of the MoxI preparation diluted 10-fold in SE buffer B100 were incubated at four different temperatures (25, 30, 37, and 55°C). The results are shown in Figures 3, 4A, and 4B.

Figure 3. Electrophoretic separation of the hydrolysis products of pHspAI2/GsaI DNA generated by the MD-endonuclease MoxI in six SE buffers at 37°C.

Lanes:

2, undigested pHspAI2/GsaI DNA;

3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13: pHspAI2/GsaI DNA + 1 μL of MoxI preparation diluted 10-fold in SE buffer B100;

4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14: pHspAI2/GsaI DNA + 2 μL of MoxI preparation diluted 10-fold in SE buffer B100;

3–4, SE buffer B;

5–6, SE buffer G;

7–8, SE buffer O;

9–10, SE buffer W;

11–12, SE buffer Y;

13–14, SE buffer ROSE;

1 and 15, 1 kb DNA ladder (0.25–10 kb).

Cleavage products were resolved in a 1.2% agarose gel in TAE buffer.

Figure 4A. Electrophoretic separation of the hydrolysis products of pHspAI2/GsaI DNA generated by the MD-endonuclease MoxI at 30, 37, and 55°C in SE buffer Y.

Lanes:

2–5, incubation at 30°C;

7–10, incubation at 37°C;

13–16, incubation at 55°C;

6 and 12, undigested pHspAI2/GsaI DNA;

2, 7, 13: pHspAI2/GsaI DNA + 0.5 μL of MoxI preparation diluted 10-fold in SE buffer B100;

3, 8, 14: pHspAI2/GsaI DNA + 1 μL of MoxI preparation diluted 10-fold in SE buffer B100;

4, 9, 15: pHspAI2/GsaI DNA + 2 μL of MoxI preparation diluted 10-fold in SE buffer B100;

5, 10, 16: pHspAI2/GsaI DNA + 1 μL of undiluted MoxI preparation;

1, 11, 17: 1 kb DNA ladder (0.25–10 kb).

Cleavage products were resolved in a 1.2% agarose gel.

Figure 4B. Electrophoretic separation of the hydrolysis products of pHspAI2/GsaI DNA generated by the MD-endonuclease MoxI at 25 and 30°C in SE buffer Y.

Lanes:

1–4, incubation at 25°C;

6–9, incubation at 30°C;

5, undigested pHspAI2/GsaI DNA;

1 and 6: pHspAI2/GsaI DNA + 0.5 μL of MoxI preparation diluted 10-fold in SE buffer B100;

2 and 7: pHspAI2/GsaI DNA + 1 μL of MoxI preparation diluted 10-fold in SE buffer B100;

3 and 8: pHspAI2/GsaI DNA + 2 μL of MoxI preparation diluted 10-fold in SE buffer B100;

4 and 9: pHspAI2/GsaI DNA + 1 μL of undiluted MoxI preparation;

10, 1 kb DNA ladder (0.25–10 kb).

Cleavage products were resolved in a 1.2% agarose gel.

Analysis of the results allowed us to conclude that MoxI exhibits maximal activity in SE buffer Y (33 mM Tris-acetate, pH 7.9; 10 mM magnesium acetate; 66 mM potassium acetate; 1 mM DTT) (Fig. 3, lanes 11–12). The optimal reaction temperature is 37°C, although the enzyme operates with comparable efficiency at 30°C (Fig. 4A, lanes 2–5 and 7–10). Under these conditions, the enzyme activity is at least 5000 U/mL. At 55°C, MoxI activity does not exceed 20% of the optimum (Fig. 4A, lanes 13–16). At 25°C, enzyme activity is at least 50% of the optimum (Fig. 4B, lanes 1–2). Notably, the new enzyme proved to be thermostable, since complete inactivation of MoxI in the reaction mixture does not occur after heating to 65 or 80°C for 20 min (data not shown).

Table 1 summarizes the activities of MoxI and GlaI in the six main SE reaction buffers for restriction endonucleases.

Table 1. Activity of the MoxI and GlaI preparations in six main SE reaction buffers for restriction endonucleases (percentage of the maximum activity).

| SE buffer | B | G | O | W | Y | ROSE |

| MoxI | 50–75 | 75–100 | 10–25 | 25–50 | 100 | 80 |

| GlaI | 75–100 | 75–100 | 25–50 | 25–50 | 100 | 100 |

Determination of the DNA cleavage position of the MD-endonuclease MoxI

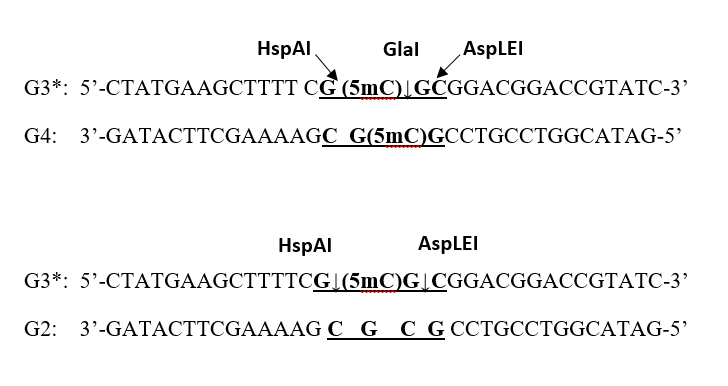

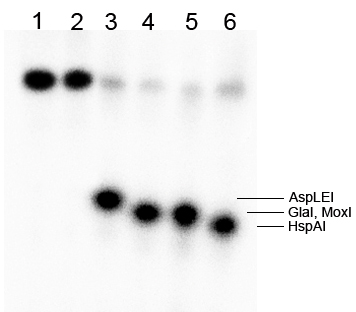

To determine the DNA cleavage site of the new enzyme, we used two double-stranded oligonucleotide duplexes that were ^32P-labeled at the 5′ end, G3*/G4 and G3*/G2 (the labeled strand is indicated by an asterisk). Duplex G3*/G4 contains two 5-methylcytosines (one in each strand), thereby forming the GlaI recognition site (underlined). Duplex G3*/G2 was used as a control, since it differs from the former only in that strand G2 contains the unmethylated 5′-GCGC-3′ sequence; thus, this duplex is hemimethylated and can be efficiently cleaved by the restriction endonucleases HspAI [14] and AspLEI [15], which recognize and cleave the sequence 5′-G(5mC)GC-3′/3′-CGCG-5′. These enzymes cleave this substrate at a distance of one nucleotide to the left and to the right, respectively, of the GlaI cleavage position (see Fig. 5A). An electropherogram obtained after separation of the cleavage products of duplexes G3*/G4 and G3*/G2 in 20% PAGE containing 8 M urea is shown in Fig. 5B.

Figure 5A. Structure of the oligonucleotide duplexes G3*/G4 and G3*/G2 used to determine the DNA cleavage position of the MD-endonuclease MoxI. The enzyme recognition sequence is underlined and shown in bold. Predicted cleavage positions for the control enzymes are indicated by diagonal arrows. The actual cleavage sites are indicated by vertical arrows.

Figure 5B. Mapping of the MoxI cleavage position on the G3*/G4 oligonucleotide duplex. The electropherogram was obtained in 20% denaturing PAGE containing 8 M urea after separation of the digestion products generated by GlaI or MoxI on duplex G3*/G4, and by HspAI or AspLEI on duplex G3*/G2.

Lanes:

- undigested G3*/G4 duplex;

- undigested G3*/G2 duplex;

- G3*/G2 duplex + 1 μL AspLEI;

- G3*/G4 duplex + 20% DMSO + 1 μL GlaI;

- G3*/G4 duplex + 1 μL MoxI;

- G3*/G2 duplex + 1 μL HspAI.

As can be seen in Fig. 5B, the MoxI cleavage position coincides with that of GlaI (marked by an arrow): 5′-G(5mC)↓GC-3′. Thus, MoxI generates blunt ends upon DNA hydrolysis and is a true isoschizomer of GlaI. The same gel autoradiogram also corroborates the result obtained earlier with plasmid substrates: the MD-endonuclease MoxI efficiently cleaves a DNA substrate containing two internal 5-methylcytosines (lane 5), whereas efficient hydrolysis of such a substrate by GlaI occurs only in the presence of DMSO in the reaction mixture (lane 4).

The new MD-endonuclease MoxI, being an isoschizomer of GlaI, can be used in epigenetic studies, in particular in GlaI- and GLAD-PCR analyses [14,15], because—unlike GlaI previously employed for these applications—it performs equally well at 30 and 37°C and efficiently cleaves the 5′-R(5mC)GY-3′ site containing two internal 5-methylcytosines. This enables more complete digestion of analyzed DNA samples in the absence of DMSO, which is required for complete cleavage by GlaI but inhibits PCR.

-

References

- SibEnzyme. Methyl-directed DNA endonucleases (MD-endonucleases). Available at: https://sibenzyme.com/product-category/md/ (accessed December 17, 2025).

- Tarasova GV, Nayakshina TN, Degtyarev SKh. 2008. Substrate specificity of new methyl-directed DNA endonuclease GlaI. BMC Molecular Biology. 9:7.

- Handa V, Jeltsch A. 2005. Profound flanking sequence preference of Dnmt3a and Dnmt3b mammalian DNA methyltransferases shape the human epigenome. J Mol Biol. 348(5):1103–1112.

- Gonchar DA, Akishev AG, Degtyarev SKh. 2010. BlsI- and GlaI-PCR analysis: a new method for studying methylated DNA regions. Vestnik Biotechnology and Physico-Chemical Biology Named After Yu. A. Ovchinnikov. 6(1):5–12. (in Russian).

- Kuznetsov VV, Abdurashitov MA, Akishev AG, Degtyarev SKh. 2014. Method for determining the nucleotide sequence Pu(5mC)GPy at a specified position in extended DNA. Patent RU 2525710 C1. (in Russian).

- Abdurashitov MA, Tomilov VN, Gonchar DA, Kuznetsov VV, Degtyarev SKh. 2015. Mapping of R(5mC)GY sites in the genome of human malignant cell line Raji. Biol Med (Aligarh). 7(4):BM-135-15.

- Chambers SP, Prior SE, Barstow DA, Minton NP. 1998. The pMTLnic- cloning vectors. I. Improved pUC polylinker regions to facilitate the use of sonicated DNA for nucleotide sequencing. Gene. 68:139–149.

- Yanisch-Perron C, Vieira J, Messing J. 1985. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 33:103–119.

- Chernukhin VA, Gonchar DA, Kileva EV, Sokolova VA, Golikova LN, Dedkov VS, Mikhnenkova NA, Degtyarev SKh. 2012. A new methyl-directed site-specific DNA endonuclease MteI cleaves the nonanucleotide sequence 5′-G(5mC)G(5mC)NG(5mC)GC-3′/3′-CG(5mC)GN(5mC)G(5mC)G-5′. Vestnik Biotechnology and Physico-Chemical Biology Named After Yu. A. Ovchinnikov. 8(1):16–26. (in Russian).

- Egorov NS, ed. Manual for Practical Classes in Microbiology. Moscow; 1995. (in Russian).

- Holt JG, et al., eds. Bergey’s Manual of Determinative Bacteriology. 9th ed., 2 vols. Russian translation; Zavarsin GA, ed. Moscow; 1997. (in Russian edition).

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1987.

- Abdurashitov MA, Chernukhin VA, Gonchar DA, Dedkov VS, Mikhnenkova NA, Degtyarev SKh. 2016. Dimethyl sulfoxide changes the recognition site preference of methyl-directed site-specific DNA endonuclease GlaI. Research Journal of Pharmaceutical, Biological and Chemical Sciences. 7(1):1733–1739.

- SibEnzyme. Kit for GlaI-PCR analysis. Available at: https://sibenzyme.com/product/glai-pcr/ (accessed December 17, 2025).

- SibEnzyme. Kit for GLAD-PCR analysis. Available at: https://sibenzyme.com/product/glad-hybrid/ (accessed December 17, 2025).